"History binds Josh [Gibson] and Satchel at the hip as the two towering figures of the Negro Leagues, but nature left them as mismatched as yin and yang. Josh was a hitter who mashed pitches, Satchel a pitcher who undid batters. Josh's power emanated from his huge arms and torso, Satchel's from his string-bean legs. The differences, however, went deeper. Josh steered clear of the limelight. Satchel lived in and monopolized it. Josh was eaten up by the limits of his ravaged knees and his Jim Crow world, consoling himself with booze, which had been legalized, and opiates, which had not. Satchel learned to cope and triumph. Josh was a player's player with a bench full of friends. Satchel played to the crowd, which made his teammates admire more than love him."

- Satchel, by Larry Tye, p 73

King Arthur. Davy Crockett. Paul Bunyan.

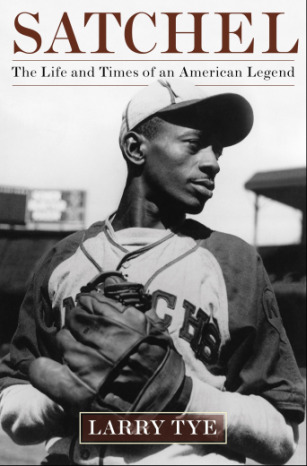

There are individuals throughout history who so inspire us that their legends grow well beyond their actual stature, becoming so entangled in the stories of their lives that it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to determine where the man ends and the lore begins. Such is the case with Leroy “Satchel” Paige, about whom Larry Tye has penned a new biography, simply entitled, “Satchel”.

For a man who may have been seen in person by more spectators than anyone else in history, there was precious little written about Satchel Paige, at least little that can be called 'reliable', anyway. Perhaps the task of unraveling the mystery surrounding the man appeared so daunting to so many. Perhaps many felt that clearing up those mysteries would take something away from the man himself. Tye has managed to do the former without sacrificing the latter, though it took him two years to accomplish it.

Having pored over every available reference on his subject, Tye sifted and sorted and deciphered all of the available information on Satchel and weaved it into not only a coherent whole, but a telling, endearing and interesting story as well. It’s well written without being pretentious or excessively verbose, making for a very accessible and easily read narrative that flows well. Tye provides sufficient background on people and places without boring you and without feeling the need to inform the reader of every possible nuance about a given individual or situation, and most important, without making the reader feel that he's gotten off track.

He manages to point out and discuss the various social injustices of Satchel’s day without sounding condescending or sanctimonious, something too many who have written about the Negro Leagues seem to feel is their duty. This makes it possible for the reader to enjoy the narrative for what it is, to appreciate the charming, nostalgic aspects, to react with distaste when he discusses racial slights and slurs, but not to become so overburdened with guilt that the reading becomes less than enjoyable. Indeed, few would read such a book if they had to fear being scolded for long-past wrongs they never committed on every other page.

Tye begins at the beginning, which is not as easy at is sounds in the case of Satchel Paige, whose birth name was Leroy Page and whose birth date was virtually anybody’s guess. I won’t ruin the surprise, except to say that part of Satchel’s mystery included the fact that throughout most of his professional life, nobody knew exactly how old he was. The birth date mystery was such a part of his legend that there was even a Trivial Pursuit card that included three possible birthdates as the clue to "Satchel Paige".

Tye describes Leroy’s difficult youth in Mobile, Alabama, one of many children in a very poor family, beholden to an alcoholic father who died young. Leroy had trouble with authority even then and spent a third of his youth in a reform school, which helped shape him into both the man and the ballplayer he would eventually become. Upon his release, he almost immediately took up with a local semipro team, was given his famous moniker (though there are even more stories as to how he became Satchel than there are potential birth dates, it seems) and as he realized that his skills could take him much farther, he began to hone them.

Trips through the minors of Black Ball in the 1920’s took him all over the South, to Mexico, the Caribbean, and eventually to Pittsburgh, to the Black major leagues, where he would become a star. Not that he stayed there long. Contracts in the Negro Leagues were looked at as something to do until something better came along, and for the likes of Satchel Paige, it frequently did. He hopped around North America, playing in Pittsburgh, certainly, but also in North Dakota, California, Colorado, and Kansas City, as he felt inclined.

Effa Manley bought his rights twice for the Newark Eagles, though he never suited up for them. He also went back to the Caribbean, playing in the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Puerto Rico, and even Venezuela, where he was nearly killed by natives, if you believe his story. It was probably Satchel, not Babe Ruth (or, as James Hirsch would have you believe, Willie Mays) who was baseball's first true international superstar, and this before he ever suited up for the major leagues.

But believing Satchel’s stories is exactly what makes writing his biography so difficult. There are lots of stories that have trickled down from Satchel Paige and other stars of the Negro leagues, and many of them, if they are true at all, are only slightly so. But they’ve been told and retold so many times that few know the difference anymore.

Part of the charm of the Negro leagues, it seems, was that in an industry that either did not have the money or did not have the interest in recording every event meticulously, the history became entangled with the tall tales, and everyone was basically OK with that. The men who played there lived their lives and spun their fables, never with malice in mind, and they made for good stories and good story tellers, which was what people wanted anyway. Why bother to point out that Satchel never really struck out Babe Ruth in a barnstorming game at Yankee Stadium? He could have, everyone knew, and that was all that counted.

Along the way, Tye describes interactions and exploits with some of the greats of both black and white baseball, Josh Gibson, Buck O’Neil, Double Duty Radcliffe, Oscar Robertson, and Cool Papa Bell, to name a few, but also Bob Feller, Dizzy Dean, Lou Gehrig, Stan Musial, and many of the barnstorming stars of Major League Baseball.

Satchel eventually made it to the major leagues, the first pitcher to break the color barrier. He had been more than a bit irked by the fact that Branch Rickey did not come calling for him, rather than Jackie Robinson, who had played barely one year in the Negro Leagues, whereas Satchel had paid his dues for almost two decades. But Satchel, besides being over 40 years old, was never one to honor a contract or turn the other cheek, so Rickey deemed that he was something less than an ideal candidate for his grand experiment.

Instead, Indians' owner Bill Veeck took a chance on Satchel and made him the American League's first black pitcher. Satchel, at 41, became the oldest "rookie" in major league history, and four years later, its oldest All Star, and then in 1965, he became the oldest pitcher in MLB history, throwing three scoreless innings for the Kansas City Athletics against the Boston Red Sox, at the age of 58. The Los Angeles Times story on the game called it, "A gimmick, yes. A joke, no."

Veeck and Paige would enjoy a life long relationship, and Paige could thank Veeck for giving him second and third chances when he wore out his welcome with previous employers, as he seemingly always did. Veeck brought Paige in to pitch for the St. Louis Browns and then later on for the Miami Marlins, a minor league team for whom Satchel pitched in his 50's.

Because he'd never saved any of his money and didn't have the kinds of sponsorship opportunities afforded to either today's athletes or white stars of Satchel's heyday, Paige never did stop pitching, really. He just kept going, barnstorming in places like Alaska, North Dakota, California, and Missouri, just to make ends meet. Even after he was finally inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971, Satchel kept on making appearances and pitching. He was paid as a consultant when a film was made about his life, but otherwise, he rarely had the luxury of not pitching if he didn't feel like it.

As far as Tye's book goes, it is a joy to read. It's his first baseball book, I believe, and he gets a few of the minute details wrong, such as referring to Joe DiMaggio as "Jumpin' Joe" or indicating that the number of games in the baseball season was 151, rather than 154, but these are minor and forgivable offenses. Tye gets the main and plain things very right, and goes above and beyond the call of duty in writing this book (as attested to by the fact that he has almost 80 pages of notes and bibliography).

Satchel Paige was the kind of interesting, incredible, lovable, frustrating, talented but flawed character that we all wish we could have known or could have been. The stories of his life, such as they are shared in Tye's book, fill out the holes in the legend probably more than Paige would have wished, but no less than his legend deserves.