Hoo-boy...

I dunno if y'all heard about this one, but Fernando Tatis hit two homers! The second one when his team was already leading by quite a little piece! A lot of people were really upset about this, apparently. Fernando Tatis owes the pitcher an apology! The nerve! Hitting a grand slam - his second homer of the game! - when his team already had a significant lead! How *dare* he??

Oh, wait, No, not last night.

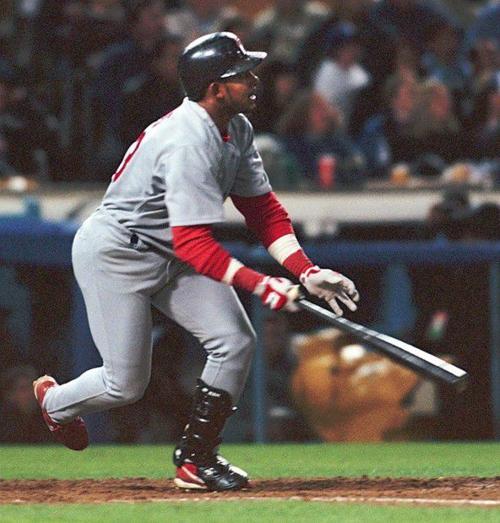

*This* game, from 1999.

In that game, Fernando Tatis SENIOR hit two homers, actually two grand slams, IN THE SAME INNING, both off Chan Ho Park of the Dodgers. In Sr.'s case, they had a 7-2 lead in the third inning - due largely to his first grand slam of the inning - and would go on to win 12-5.

Actually, now that I think of it, nobody told him he should have laid down and coasted after that first homer. MLB actually celebrates it! Someone writes a story and shows the video every year on the anniversary. Sure, it was a smaller lead, earlier in the game, and he swung at a 3-2 pitch (his first one came on a 2-0 pitch), but still. The parallel is there at some level.

OK, it's weak, I admit, but I'm trying to make a point here:

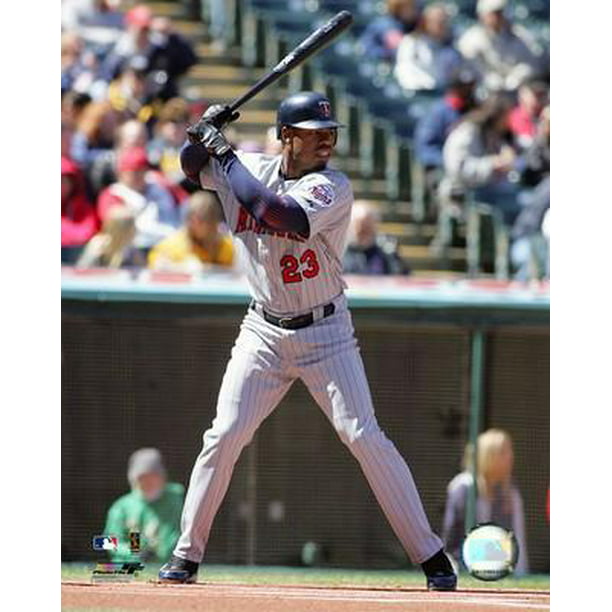

Fernando Tatis The First had easily his best season in 1999. In January, his son was born, which was probably pretty exciting. After floundering with the Rangers for a couple of seasons, he'd been traded to the Cardinals at the deadline in 1998 and played well enough down the stretch and in spring training in 1999 to win the starting 3B job outright.

All would turn out to be career highs, as he was never fully healthy again. Sad face.

He played only parts of the next four seasons, hitting just 37 homers *total* from 2000 to 2003, then missed two whole years, then played a few games with the 4th place Orioles in 2006, then missed all of 2007, and then caught on as a part timer with some forgettable Mets teams (...or anyway I had forgotten them.) in the late 2000s. He won the dreaded Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year award in 2008, but even at that, he hit 11 homers in 92 games and was already 33 years old. His star had passed.

In short, Fernando Tatis The Younger should hit 'em while he can. Life is too short. Baseball careers are too short. For every Ken Griffey or Barry Bonds, a good player whose son would turn out to be one of the all-time greats, there are probably a dozen Tim Raines Jrs and Josh Barfields and Sean Burroughs and Kyle Drabeks who never make much of a mark in the majors, despite the accomplishments of their parents. Tatis and Vlad Guerrero Jr. and Bo Bichette all look like wonderful young players, the future of MLB. All three have already spend time on the injured list. Anything can happen.

The real problem with these unwritten rules comes out in the quote from Rangers' manager Chris Woodward:

“I think there’s a lot of unwritten rules that are constantly being challenged in today’s game. I didn’t like it, personally. You’re up by seven in the eighth inning; it’s typically not a good time to swing 3-0. It’s kind of the way we were all raised in the game.”

Except we were not all raised that way. Apparently in Woodward's home territory in Southern California, and for that matter in Padres' manager Jayce Tingler's original stomping grounds in Missouri, maybe kids are raised not to ever swing at a 3-0 pitch. Even when it looks like a meatball and you've got the bases loaded. Or not to try to hit homers when your team is already winning by several runs.

But suburban American white kids often have it drilled into their heads that they should be calm and dignified and that they should not show up the opposition and that they should "act like they've been there before" even if they haven't. You hit your homer and keep your head down and trot around the bases - not too slow, not too fast - or he'll drill you (or worse yet, your teammate) in retaliation.

Well, Tatis hasn't been there before, and he wasn't "raised in the game" that way. (Plus, apparently he missed the "take" sign. :-/ ) He's 21, and he'd never hit a grand slam in the majors before. He'd never homered on a 3-0 pitch before. When you're that young, it's all new, and when you're that talented, you should be allowed to explore the depths of that talent.

Not for his sake, or anyway not just for his sake, but for ours. The fans. We're the whole reason he's here, he has this job to entertain us. And we want some damn excitement once in a while! This friggin' pandemic is hard enough on all of us without having to suffer through watching a talented youngster take a get-me-over fastball down the pipe on 3-0 with the bases loaded. Take a chance and enjoy it while you can!