This was a weird year.

In an effort to minimize travel, and thereby minimize potential exposure to COVID-19, Major League Baseball implemented an odd, 60-game schedule that allowed teams only to play the other four teams in its own division and the five teams in the corresponding geographical division in the opposite league. This means, for example, that the Yankees played both the Atlanta Braves and the Miami Marlins, but not the Tigers or the Indians, who are both obviously a lot closer, not to mention in their actual league.

Additionally, as another concession to the disease and its effects on us all, we have a new, 8-team-per-league postseason format in which the winners from each division and their runners up all make the postseason, plus the two teams with the next best records. This gives us not one but two teams with losing records (the Brewers and the Astros) who actually have a chance to win the World Series.

Which sucks.

The decisions on who makes the playoffs are, in themselves, somewhat nonsensical. Here are the three actual in-practice regional quasi-leagues this season (East, Central and West) and how they stack up against each other. The teams in bold are the ones going to the actual playoffs.

You can probably see a couple of things wrong with this picture right away. Almost everyone from the Central got in (7 of 10 teams), while the Phillies, for example, have almost as good a record as the Astros and Brewers, whom they never played. If MLB had chosen instead to take, say, six teams from each regional league, and give two teams a bye for the first round or something like that, instead of doing it the way they did, Philly might be in the playoffs right now instead of one of those teams. Not that they would deserve to be, but still.

Furthermore, the Giants had the exact same record as the Astros, against the same competition, but did not make the playoffs. Granted, their head to head records (Houston won two of three) would likely have given the advantage to the Astros anyway, but if MLB had chosen instead to take the best five teams from each region, plus one more to round out the 16 - which probably would have been more fair - then the Giants would have been in and the Brewers out. And the Phillies would still be watching the playoffs from their couches, as they should be.

As it is, in this reality, the teams will all play a three-game series, entirely at the home stadiums of the higher seeded teams in the first round. Then, if they get past that, they will play the ALDS and NLDS at neutral sites in California and Texas, as shown below. As a result, we have a playoff picture that is murkier that it has ever been, heading into the first day of competition.

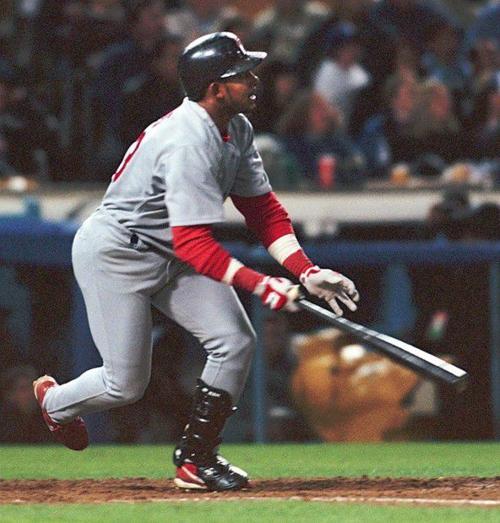

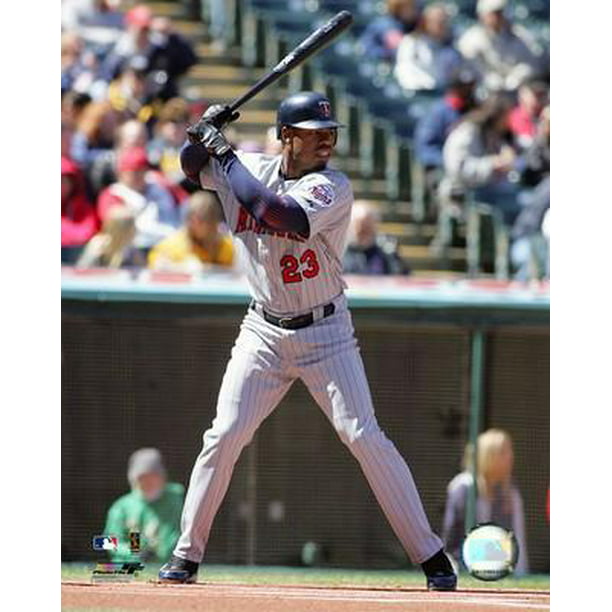

Another problem with this format is that the seeding was done based on division winners and runners up getting the highest seeds, rather than by best overall record. So the Twins are a #3 seed, even though they had the best record among the teams against whom they actually competed. They're playing the Astros, who had a losing record, but are seeded above both the White Sox and the Jays, both of which had winning records, because the TrAshtros finished second in the AL West, which was pretty awful outside of Oakland.

Part of the reason for this format is that the shortened season and limited competition sort of inhibits our ability to tell how good a team is. Sure, Gerrit Cole seems to be the ace the Yankees signed for a bajillion dollars in the offseason, but he was 5-1 with a 1.69 ERA against teams that did not make the playoffs (Phils, Sawx, O's and Nats), and 2-2 with a 4.10 ERA against teams that did (the Braves, Rays and Jays). How would he have fared against the A's, or the Twins? We may never know, especially if the streaky Yankees can't advance past the first round.

But I was curious to see who would have led their respective "regional leagues", and more important perhaps, who might have "won" the awards if the players were being compared to their regional peers this year instead of to players they never faced until the postseason, or maybe not at all. I'll look at the position players today and will save the pitchers for tomorrow.

Position Players:

So here are your hitting leaders!

Luke Voit and DJ LeMahieu would still have their respective crowns, but Tim Anderson and Donovan Solano would also have won batting titles.

Interestingly, LeMahieu takes the title over Anderson in real life this year, the reverse of 2019, which marks the first time since 1956-57 that the same two players have finished #1 and #2 in the AL batting title race, albeit not in the same order each year.

At that time it was Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams, and of course Mickey won the Triple Crown in 1956, including his only batting title and the first of his three MVPs. Williams hit .388 a year later and won the "slash line triple crown" (leading the AL in average, on-base percentage and slugging percentage) but finished 2nd in the MVP coting for the 4th time, each time losing to a Yankee (twice to DiMaggio, once to Mantle and once to Joe Gordon).

Good times! Anyway, back to 2020...

Manny Machado would have led the West in RBIs! Mike Trout in homers! In the Central, Jose Abreu would have two of the three triple crown pillars all to himself, instead of the just the AL RBI crown.

Donovan Solano seems to have followed the Gio Urshela path to becoming a major league regular. Both were signed as amateur free agents as teenagers from Colombia. Both bounced around multiple organizations for many years, primarily as a glove-first backup infielder. And both somehow just learned how to hit in their late 20s. Urshela famously filled in for the injured Miguel Andujar, and has hit .314 with 27 homers in 650 plate appearances the last two seasons, while remaining a plus defender at the hot corner. Solano, meanwhile, has hit .328 with 28 doubles and 7 homers in over 400 at-bats the last two seasons, and by rights should now have a batting title to his credit.

Jonathan Villar is also an interesting case: He was traded from the Marlins to the Blue Jays for a PTBNL in mid-season, and stole a total of 16 bases. (The Jays sent Griffin Conine to Miami to complete the trade, apparently having decided that having four sons of former MLB or international baseball stars on their roster was enough.) On paper it looks like Villar amassed fewer than 10 steals each in the AL and the NL, but in reality, he stole more bases than anybody he played against in the eastern "League". His 16 steals were one more than Trevor Story had, and yet Story has some black ink on his ledger, for leading the Senior Circuit, whereas Villar does not get credit for the second time he led his competition in steals (he had 62 in 2016 with Milwaukee, which easily led the NL).

I have also listed the Wins Above Replacement leaders from both Baseball Reference (bWAR) and Fangraphs (fWAR) as well as the position players who I thought might be considered the Rookie of the Year for each region. In this case, the bWAR and fWAR in two of the three regions both agree on Freeman and Betts. Mookie Betts leads both WAR types, both in the NL and in the "west" thanks largely to his stellar defense in addition to his excellent hitting and base running skills. Despite not leading the West in any of the individual stats (he hit .292 with 16 HR and 10 steals), he appears to have been the best overall player, in his or any division or league.

As for the Central, if the BBWAA were deciding they would probably give it to Abreu, who led middle America in both homers and RBI. But Jose Ramirez essentially carried the entire Cleveland offense, and played stellar defense at the hot corner to boot (or, you know, not to boot, which is what you're trying to do when you play third base), so I might give the MVP to him if I had the chance.

And Now for the Rookies...

EAST: Alec Bohm did not play the whole year but when the Phillies called him up, he hit .338 in 44 games with gap power (11 doubles, 4 HR) and didn't totally embarrass himself on defense. Only one MLB rookie with at least 160 at-bats has hit better than that in a season since Ichiro burst on the scene hitting and AL leading .350 in 2001. (Trea Turner hit .342 in 307 at-bats in 2016.) Maybe if the Phillies can upgrade some of that dumpster fire of a bullpen of theirs, they'll have something to build on next season. OK, probably not.

CENTRAL: Luis Robert hit just .233, but keep in mind that the major leagues as a whole hit just .245, the lowest mark since 1972 (.244), which was so terrible that half of the owners voted to implement the DH and old people have been whining about it ever since. Also keep in mind that Robert hit 11 homers and 8 doubles, stole 9 of 11 bases in just 202 at-bats, and played stellar defense in center field. Extrapolate that out to a full season and you're talking about a Gold Glove rookie knocking on the door of the 30-30 club.

WEST: Kyle Lewis is another rookie centerfielder, albeit not as good defensively as Robert. He also hit 11 homers, and hit .268 and took a walk more than once every other game, giving him the best OBP among rookies in the AL.

Tomorrow I'll look at the pitchers and see who I think should win the MVP and Cy Young awards for each region.